Click here to download this story as a PDF

Ifaa Birra plans to buy a tractor. Not unusual for a farmer, but that’s only part of the story. And a tractor is not something Ifaa thought about much until recently.

“I have a large area of land, but my production was low,” Ifaa says. “Crops didn’t hold properly, and they failed. I would save the little crop that survived to feed my family as it was not enough to sell it in the market for income.”

Seeking information that would help him increase his yields, he joined the Bora Denbel Farmers’ Co-op Union, which is mainly engaged in grain trading (maize/corn, common bean/haricot bean, wheat, teff, etc). There he met with local agriculture experts who showed him new approaches to farming.

“I joined the union six years ago,” he says. “We received different types of trainings on farming. The union showed us how to manage and improve the performance of our crops, so our crops don’t keep failing.”

The union also happened to offer a better market for Ifaa and his fellow farmers.

“By selling to the union, we get an extra 15% income,” Iffa says. “If we sell directly to the market, we lose this extra 15%. For example, if we sell 100kg of wheat for 100,000 birr, I get an additional 15,000 birr just for selling to the union and this means more money for my family.”

“I joined the union six years ago.We received different types of trainings on farming. The union showed us how to manage and improve the performance of our crops, so our crops don’t keep failing.”

– Ifaa Biraa

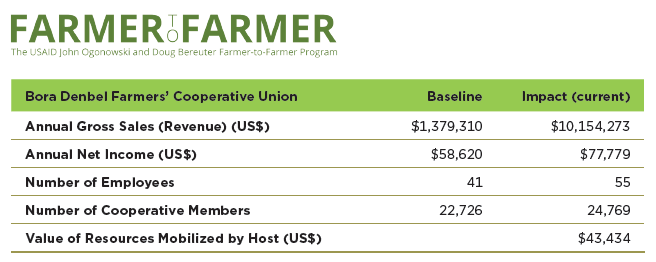

And Ifaa’s story might end there, with a tractor in his future. But the union, which serves 22,726 members in 87 primary cooperatives regionally, was looking for long-term solutions.

“The goal of this union is to support farmers so they are more productive,” says Adem Jambo, deputy manager of the Bora Denbel Farmers’ Co-op Union. “We provide farmers with improved seeds, fertilizers and technical support in the field.”

And they wanted to do more for farmers, operate more efficiently, and see how they might strengthen an already fairly healthy operation.

So, they turned to U.S. Agency for International Development’s Farmer-to-Farmer, or F2F, program that matches U.S.-based volunteer experts with hosts—farmers and producers who have specific technical needs that F2F has the capacity to address.

Catholic Relief Services implements F2F in six countries, including Ethiopia, where CRS program staff located volunteers to work alongside the union to understand its needs and plans for future growth.

The union wanted information about proper management of financial transactions, improving documentation and recording accounts payable and receivable. The union also wanted to fill skill gaps and transition from manual to computerized financial management.

“We started working with CRS in 2014,” Adem says. “They gave us trainings about farming practices.”

Adem was impressed, not only with this new source of information, but the F2F approach.

“They didn’t just come and take over what we already had, rather they listened to our needs and together we were able to choose the best ways of empowering farmers. One person can only achieve something if they are capable, and CRS provided this capacity through trainings. These trainings are more valuable than money, the F2F volunteers stayed with us for three weeks to give us in-person, practical trainings. Our farmers are very happy.”

Adem says the benefits they were able to pass on to their members rapidly bore fruit.

“There is a big difference in their performance,” he says. “Three years ago, the total number of quintals produced was 12,000 quintals of wheat by 150 farmers. This year our farmers produced 50,000 quintals of wheat by 356 farmers. We have received appreciation from the government and other entities because of our growth.”

That was just for wheat. They also produce maize and teff.

Back office and management ideas, also sought by the union, turned out to be some of the most important information for the union. To help its farmers grow, they knew the union would need to grow. They particularly enjoyed one new concept.

“Marketing, before we didn’t really consider promoting our work so publicly. Now we are taking part in exhibitions and bazaars in different cities.

We use these events to show the quality of our seed and our maize, wheat and teff flour,” Adem says. “CRS also gave us trainings on warehouse management. When the government saw how productive we were being, they gave us additional warehouses to store our food. We didn’t know much about managing warehouses, it is only after we received trainings from CRS that we learned so many things.”

As union staff saw that many of the new approaches simply meant tweaking what they were already doing, other information came as welcome news.

“For instance,” says Adem, “we didn’t know anything about the First in First Out, or FIFO, method. We didn’t know about the importance of hygiene, ceiling, leveling, fumigating, conducting germination and moisture tests. For example, we used to keep reject materials in the warehouse, but CRS taught us that extra material should not be stored in the warehouse. In the past when we are not loading or unloading food, we always kept the warehouse closed, CRS taught us warehouses should be kept open during the day, so the heat doesn’t cause contamination.”

“We had a factory but no skilled labor to control flour quality,” Adem says. “We asked CRS to provide us with technical assistance for our factory employees. Our employees received a three-week training on wheat flour quality control.”

CRS’ decades of agricultural work and service makes it a natural fit for USAID’s unique F2F program. The method of first listening to and learning from local agriculture experts, farmers, farm support entities like the co-op union, and other producers along the value chain, helps speed up acceptance of new concepts and methods during the short two- to four-week sessions the volunteers offer their hosts.

“The change is real, it is tangible, we can feel and see it,” Adem says. “A lot of the areas CRS gave us trainings on would have stayed as theories on our minds, it is only after CRS’ encouragement and support that we were able to change it to practice.”

Adem says the three weeks will have long-term effects well into the future. Two prime co-op union goals—growth and sustainability—were clearly met.

“They say instead of feeding someone, show them how to make the food, and they will eat forever. This is what CRS has done for us,” Adem says. “We are changing the lives of farmers in this community. A farmer under the union has a minimum of a motorbike and one cattle, they are doing really well.”

Of course, the benefits of healthy farms have impact well beyond the pastures and fields.

“The community now has access to quality food, with low prices,” Adem says. “So, production is not only increasing among our farmers but we are growing as a community too.”

Another key and common sign of sustainability following a host-volunteer session is that the Farmer-to-Farmer concept continues among the farmers themselves as a sort of de facto agriculture extension service. According to Ifaa

Birra, they share what they’ve learned from the union with their neighbors.

“I have shared what I know to 15 farmers,” Ifaa says. “One of these farmers was so successful that he got 44 quintals of wheat from 1/4 of a hectare, before that he was only getting about 11 quintals.”

Farmers turn to USAID’s F2F program because they know it’s always better to work smarter than harder.

“Since the income I am receiving is good, I plan to buy a tractor soon, so I don’t have to spend so much physical effort in the farm.”

The CRS F2F program is a USAID-funded program focused on reducing hunger,

malnutrition, and poverty across six countries: Benin, Timor-Leste, Ethiopia, Nepal,

Rwanda, and Uganda. The program runs from 2019-2023 and aims to generate

sustainable and broad-based economic growth in the agricultural sector. U.S. volunteers

with agricultural expertise share skills and help build capacity for farmers through

short-term training and technical assistance projects resulting in more productive,

profitable, sustainable, and equitable agricultural systems.

Photos by Melikte Tadesse/CRS